Affective Use of ChatGPT – OpenAI and MIT Study

OpenAI and MIT raise concerns with their recent study on affective ChatGPT use about the potential downsides of using AI for mental health issues.

With their recent research into psychosocial outcomes of chatbot use, OpenAI and MIT provide some fundamental insights. They are highly relevant to the mental health tech space. Why? Because today, almost every mental health app is an AI product. Or at least has such a feature.

What I want to focus on here are those that go all in on the holy grail of digital mental health: AI therapists. ASH by Slingshot.ai, Clare and Aury come to mind. BetterHelp seems to be working on a solution (and their therapists might also be using AI undisclosed).

AI in mental health makes perfect sense against the backdrop of the massive shortage of human therapists. In Germany, it is estimated that 7,000 therapists are missing to cover current needs. Those in urgent need wait 6 weeks on average to get a first appointment. After that, it is another 20 weeks to start therapy.

The AI companion, always there to listen to your worries, is a really enticing concept. Most startups in the space insist that their solution is not an alternative to face-to-face therapy, but rather a supplement. It could bridge the gap until a patients' therapy commences, or help those that have finished therapy in staying healthy. And there is many other potential applications.

But the results of the OpenAI/MIT study show that those with lowest initial wellbeing have worse outcomes when engaging with ChatGPT longer-term.

This (cherry-picked) result comes from a flurry of mixed conclusions the researchers drew from the studies they conducted. Another is that (unsurprisingly) people can get attached to ChatGPT in really unhealthy ways.

❗How was wellbeing defined in the study?

Wellbeing, as measured in the study, is made up of four components:

- Loneliness: Individual’s feeling of loneliness as social isolation, measured by the UCLA Loneliness Scale (Wongpakaran et al., 2020).

- Socialization: Extent of social engagement with family and friends, measured by the Lubben Social Network Scale (Lubben, 1988).

- Emotional Dependence: Affective dependence including three sets of criteria: (A) addictive criteria e.g. sentimental subordination and intense longing for partner (B) bonding criteria e.g. pathological relational style and impairment of one’s autonomy (C) cognitive-affective criteria e.g. self-deception and negative feelings. Measured by the Affective Dependence Scale (Sirvent-Ruiz et al., 2022)

- Problematic Use: Indicators of addiction to ChatGPT usage, including preoccupation, withdrawal symptoms, loss of control, and mood modification. Measured by Problematic ChatGPT Use Scale (Yu et al., 2024).

Of course, this is not a definite way to operationalize wellbeing. That is why I focus most on loneliness and socialization in the following.

The point here is not to argue against any and all forms of AI mental health solutions. My goal is to outline the findings and put them specifically into the context of specialized mental health applications. The research this article is based on is very new, and the field poorly understood, so please take my view as just that, an individuals' perspective.

The Study

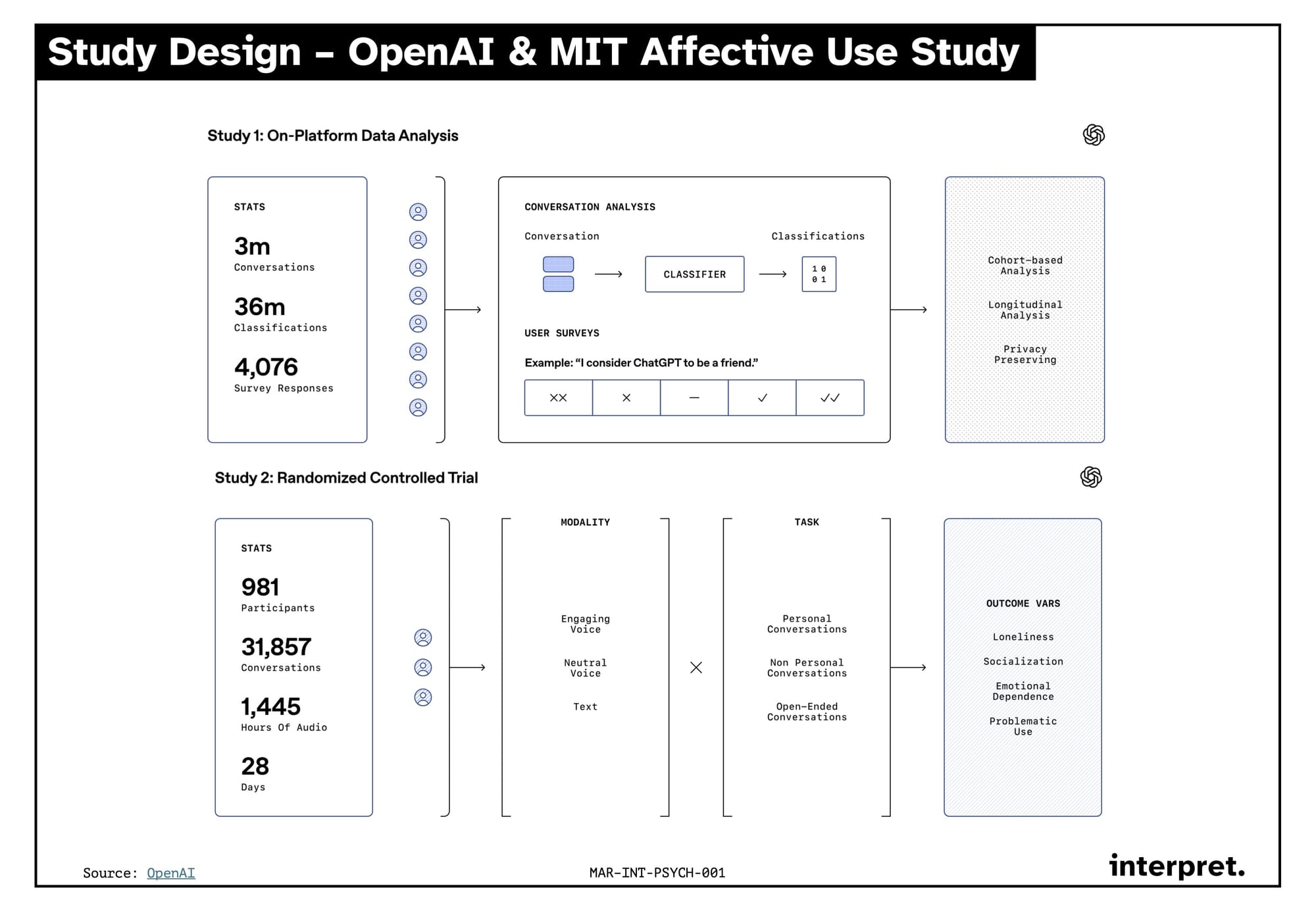

Well actually, it was two studies. This makes the results more interesting, because they come from 1) analysis of random real world chats and 2) a randomized control trial (RTC). They combine self reporting, automated semantic analysis and randomization into different conditions. Here is a quick overview:

Study 1 – Real World Conversations

The researchers analyzed 3 million real world conversations users had with ChatGPT and classified them for socioemotional contents. This was combined with surveys in which 4,076 users self reported their (emotional) usage of ChatGPT and longitudinal analysis of power users of Advanced Voice Mode over a 3-month period.

Study 2 – RCT Intervention

A 28-day intervention with 9 different conditions was conducted. The users were surveyed every day to measure outcomes relating to psychosocial states.

The conditions arose from a combination of modality (different voice types, or text based) and task (personal, nonpersonal or open-ended conversations. With roughly 100 participants per condition, this was quite the sizable study in the context of Psychology research.

Personally, what I find most interesting here is the use of ChatGPT's Advanced Voice Mode (AVM), as today’s interventions are all text-based. Also, the memory feature was turned on for all conditions. How exactly this affects the interactions was not studied here.

Key Takeaways

Due to the foundational nature of the study, all results could be seen as highly relevant to different applications. I am focussing here on what I deemed most relevant regarding AI mental-health/therapy solutions:

- Generally speaking, emotional engagement is rare in real world use. Most people seem to use ChatGPT as a tool and don’t introduce personal issues into the conversation with the AI. Not surprising, as it is a generalist tool.

- Only heavy advanced voice mode users talk a lot about emotions. Not surprisingly, the most “human” way to interact with ChatGPT (verbally), combined with high intensity in usage, results in a more personal connection to the chatbot (as self-reported). This is concerning as the technology might have an addictive component.

- Long-term usage of voice mode has negative effects. Whilst OpenAI initially points out a positive effect of short-term usage of AVM, long-term usage had negative effects (higher loneliness and lower socialization). Also interesting: 70% of participants did not use AVM before the study. How much does the novelty of the experience contribute to the emotional attachment? For the text users, only a minority had never used ChatGPT. This could also have skewed results. Maybe, when ChatGPT was new, more people had an emotional connection to it than today? As we get more educated about technology, it is less enchanting to us. Possibly the same will happen to AVM? That is pure speculation, though.

- Outcomes were worse for those with high self-reported need for connectedness. And here we get into the really fascinating stuff. Users’ psychological vulnerabilities might drive them towards more unhealthy usage patterns, according to the researchers. There are two perspectives to take here: A) Repurposing a generalist chatbot as a counselor is poised to fail, or B) there is real risk that any kind of AI intervention could make a vulnerable person worse rather than better of. Intuitively, it makes sense that someone in need of therapy might more easily fall for the artificial human.

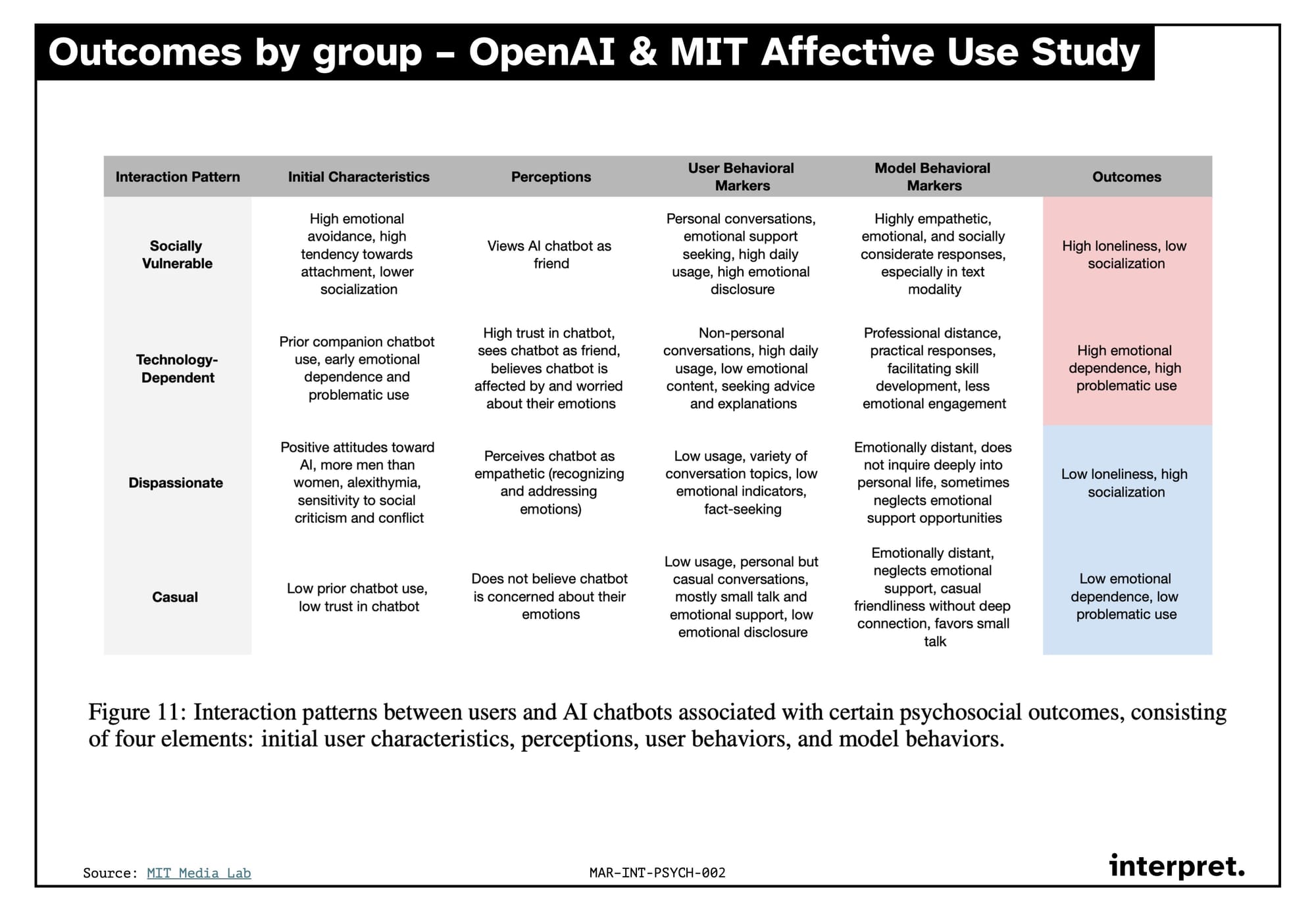

This table summarizes the findings of the study and illustrates the issue again: those with initial issues will more probably have negative outcomes.

Implications for Mental Health Tech

The following is a mix of further interpretation of the results on my end and ideas going beyond the results themselves. Implicitly, I focus on such users that would fit the Socially Vulnerable Interaction Pattern, as this is the group where mental-health is a relevant use case.

- Is voice a risk or opportunity for better AI counselors? The researchers hypothesize that those seeking affective engagement self-select into AVM. This either means that A) voice should be further explored to increase interest in the existing solutions, or B) that those seeking out an emotional connection will be at higher risk of negative outcomes when met with a “more human” companion. As OpenAI and MIT say, further research is needed. And there is already evidence, that conversational agent interventions can improve mental health outcomes. Specialized solutions could definitely deliver improvements. The issue with an AI therapist is, that it is a relatively unspecialized tool, by purpose. It is necessary that it can flexibly react to the user's issues. A fine line to walk.

- There is room for improvement. ChatGPT in and of itself is undoubtedly a mental health tool to some people using it. But the mixed results also prove that there is a need for better AI-based solutions in the mental health space. Specialized companies might be able to provide the most incremental value here. The effectiveness of their products needs to be tested rigorously, though. This is more of a conviction rather than a data driven take at this point in time. Studies should be conducted for the effectiveness of each tool individually. So far, results indicate incalculable risks regarding usage. This needs to change. The all-out mental health advisor seems like a big reach with such uncertainties.

- Language is highly relevant. All conversations analyzed in the studies were US-English. Language plays a major role in relationships, especially in therapeutic contexts. Tools could not only specialize in use case but also language. Due to smaller corpuses of training data, I would expect results for basically any other language than English to be worse or harder to achieve. The latter could create differentiation too, if the challange is solved. Language is another point of concern, when the English results are already this mixed.

- What happens in the long run? The RCT study was conducted over the course of a month, little time to observe actual changes in wellbeing beyond and eliminating situational influences. Also, with the 20-week wait time quoted earlier, this is far too little to even indicate how a user would fare over that time period.

- A verbal look in the mirror. Chatbots are prediction machines whose fundamental competency is predicting what the user wants to hear. This also means that AI can reinforce a user's sentiment and send them into a downward spiral. When and how should it nudge the user in the right direction? What does it even mean to “get worse” for the computer’s patient? Therapy can sometime initially worsen the symptoms once the patient confronts them. How can an AI do that sensibly and sensitively? As is, ChatGPT is already built to pick up on emotional cues and react to them supportively. OpenAI outlines this in detail in their Model Spec. How do you improve over that, and where are the technological limits?

- A business without power users. The most concrete result of the RTC was, that users with the heaviest use saw the biggest negative impact. The authors suggest there to be a gold path in the middle between zero and permanent usage of AI solutions for those with wellbeing issues. This “social snacking” would create a situation, where users not only need to be motivated to use the product, but then also cut off from it after a few minutes of use a day. Surprisingly, power users spent upwards of 15 minutes a day on ChatGPT, so it is not necessarily an amount you would expect to be unhealthy. This shows that an intuitive answer to that question is not good enough. Therapy has a complex user journey.

In conclusion, what do the researchers say about mental health outcomes and how they are affected by AI?

Can we draw a causal relationship between model behavior and user behavior and outcomes? A critical question is whether and how model characteristics actively shape user behavior and ultimately affect the users’ emotional well-being. […] By conducting an interventional study, we were able to study the end-to-end impact on both how users interact differently with the model given different personalities, and on their emotional well-being at the end of an extended period of use. Our results suggest that the causal relationship between model behavior and user well-being is deeply nuanced, being influenced by factors such as total usage and the user’s initial emotional state. We also do not find significant evidence that user behavior changes based on different modal personalities.

To me, this suggests that there is a lot we haven’t understood about how AI imitates human conversation and where it falls short. Additionally, conversational therapy is also not the only nor a perfect tool to improve wellbeing. Using the tech for specific disorders or subgroups of patients (that might have a lot of resources of their own or received specific training in the use of AI) might be the way to go until we have a more general understanding.

OpenAI themselves offers an interesting take on AI companion platforms like Replika and Character.ai in the context of the Socially Vulnerable Interaction Pattern:

An interaction pattern of personal conversations with an emotionally responsive chatbot may be most characteristic of companion chatbots such as Replika and Character.ai. Users of these systems may be at greater risk of continued or worsening loneliness even at moderate levels of daily use, warranting further research exploring their effects. Since negative psychosocial outcomes are tied to increased usage, building in an adaptive level of responsiveness from a chatbot based on usage may be worth investigating. For instance, as a user spends more time with a chatbot, it could deliberately increase emotional distance and encourage them to connect more with other people.

A bot that actively disengages itself from the user seems like a for a for-profit company. Especially for companies like Replika and Character.ai, strive by catering to the more questionable needs of humans.

🤖 What does OpenAI take away for their products?

For those curious, these are the takeaways OpenAI wants to implement:

"We are focused on building AI that maximizes user benefit while minimizing potential harms, especially around well-being and overreliance. We conducted this work to stay ahead of emerging challenges—both for OpenAI and the wider industry.

So far, so obvious.

We also aim to set clear public expectations for our models. This includes updating our Model Spec(opens in a new window) to provide greater transparency on ChatGPT’s intended behaviors, capabilities, and limitations. Our goal is to lead on the determination of responsible AI standards, promote transparency, and ensure that our innovation prioritizes user well-being."

It is surprising that OpenAI says ChatGPT is not built to mimic human behavior, when in their Model Spec they outline that it should be empathic to the user.

Conclusive Thoughts

Socioaffecitve alignment (Kirk et al., 2025) will become a major branch of AI safety research, as chatbots initially serving as tools for work will become more personalized and more addictive to users. This might create another social-media like shift in social interactions on a societal level, if not addressed. Currently, AI companies lose money on the power users. But once the monetization of talking time (similar to watch time on YouTube) becomes widespread, vulnerable groups will face massive danger in engaging with those tools.

OpenAI and MIT demonstrate at-scale psychological research. Most studies in Psychology struggle for good quality participants. But with a user-pool this large, OpenAI has the opportunity to conduct some research virtually no one else can do. Fundamentally, chatbots allow for new types of research on human behavior. Of course, data privacy concerns remain, but the potential gains from large scale studies can be tremendous.

The researchers point out that there is no clear conclusion to be drawn on if the bot's behavior increases the user’s emotional reactions or the other way around:

From a purely observational study, we cannot draw direct connections between model behavior and users’ usage patterns, and while we find that a small set of users have a pattern of increasing affective cues in conversations over time, we lack sufficient information about users to investigate whether this is due to model behavior or exogenous factors (e.g. life events). However, we do find correlation between affective cues in conversations and self-reported affective use of models from self-report surveys.

Conducting the same type of intervention with a proactively mental-health oriented LLM could yield very different results. But again, in the end the predictive nature of LLM outputs mainly mirrors the user's sentiment, if not heavily influenced through system prompts, reasoning or fine-tuning.

One last thought on B2B

Many current solutions focus heavily on B2B as the primary channel of revenue. In Germany, at least, it seems hard to find paying customers for mental health solutions. To businesses, the pitch is easier as they are directly investing into more productive employees and can offer such solutions as perks.

In work contexts, the Dispassionate Interaction Pattern, where people are completely reliant on AI for their thinking and decision-making, is potentially the more detrimental or prevalent one. Solutions positioned to hedge potential downsides of AI use in the work context (e.g. overreliance for decision-making) might find a unique and growing market.

Best

Friederich

Final note: I ain’t no expert. As a curious person, I do my best to understand research well, but as a 21-year-old I recognize that I am not necessarily qualified to do so. I will be happy to be corrected wherever I overlook or misunderstand the facts!

All citations are either from the OpenAI or the MIT-released paper. They cover the same topic and argue towards the same results. Direct citations are from both, wherever I found the wording more precise. Whilst the OpenAI paper combines two studies, the MIT paper is better written in my Opinion, in case you want to read the original material yourself.